Knowing When to Give Up

Toxic motivators and Sisyphean cults

The aging rockstar… the short guy who hopes to one day make it in the NBA… the talentless, tone-deaf girl who imagines her flat voice makes her the next Céline Dion… the 50-year-old divorced guy who frequents nightclubs, obsessively hitting on 20-year-old students. These are examples of people without situational or self-awareness, those who refuse to let go of truly hopeless endeavours when they must.

The perfect example of deluded optimism is the gambler who can’t seem to get that he can never win against the house, and that despite his occasional small wins, the more he plays, the more he loses overall — mathematically, objectively, undeniably.

Granted, old rock stars can still be cool, as long as they adjust their style according to age. If you saw Mötley Crüe in their 60s dressed up in their flashy androgynous costumes from their 80s appearances, performing in that hyper-sexualised rockstar flamboyance, then the lack of dignity would be the least of their problems — their main concern would be lower back pain.

The more you deludedly cling to pursuits you can’t win, the more you struggle needlessly, and the more you lose out on other, lesser opportunities whose success is more probable.

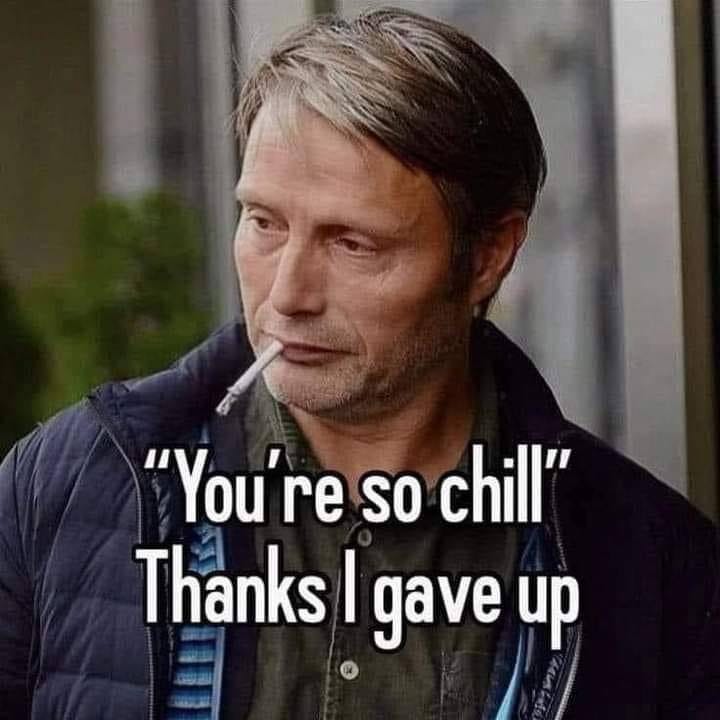

When you finally let go of your obsessions for accomplishments beyond your reach, you finally achieve the highest of contentments: peace.

Virtuous pursuit

Indeed, not giving up can be a virtue when the goal is improbable yet worthwhile, but it can also be a crippling weakness when it’s practically impossible.

What are you not giving up on? Is it a worthy, ethical goal with a bigger picture, or is it a shallow obsession you hope will bring you hollow self-aggrandisement and pride?

What do you think a specific goal might say about you? Is succeeding (or failing, for that matter) actually meaningful? Does it grant you any true worth or virtue? Is the need for “success” as a prerequisite to feeling worthy a mark of a truly worthy person? Isn’t virtue success in itself?

And how probable is it that you’ll succeed? Some goals are completely impossible, and success is realising you can’t win. For example, you can’t use your fists to fight against a storm. If you think you can, then the storm is the least of your problems.

Γνῶθι σεαυτόν.

Gnōthi seauton.

Know thyself.

Self-delusion

I see men in their 70s dyeing their hair, which makes them look like old women, desperately denying reality and missing out on the dignity of aging gracefully. I see similarly aged men driving around in red sports cars with gay loud exhausts, which is a desperate cry, a begging for cheap attention from impressionable idiots, like an insecure teenager would. I see ungifted women desperately addicted to body modification and insanely unnecessary Botox addictions, as if youth and physical attraction could ever be restored. Granted, the only margin you have to improve your physical attraction is physical fitness, and it’s commendable to keep working out at any age. But you need to manage your expectations according to age. Even fitness is reliant on your genetics, physical capacity, your early-age developmental window, and ultimately, your age.

If you are to keep a firm grasp on reality, you must know and accept your realistic abilities and limitations.

With the gambler’s fallacy guiding you, you keep gambling since you assume that the more you lose, the more probable your upcoming win becomes, as if such a win would make all the inevitable losses worth it. Most of the time, a win (or how you imagine winning) is so improbable that it is impossible to attain within your lifetime — or, even if you are astronomically lucky enough to get it right (and almost everything is luck), it won’t be worth all the times you tried and lost just to win too little too late.

When you bet against the odds, and each time you pay a grave price for losing, there’s a point where you have to consider quitting — it would be the prudent, intelligent, and courageous thing to do.

Sometimes, you just have to cut your losses and give up.

Giving up frees you from the stress and anxiety of fighting lost battles. It’s about shedding the false hope that keeps you deluded, anxious, and hopeless. Yes, you have to be truly hopeless to create and cling to false hope. And this hopeless hope is what erodes your self-esteem because your subconscious knows that you refuse to face reality due to cowardice.

There is freedom in letting go.

If nothingness is the only thing that can bring you peace, then let it be.

Energy

Giving up on something does not mean giving up on everything. Quite the contrary. When you give up on one thing, you discover new available energy to allocate elsewhere.

Not giving up and not cutting your losses deprives you of a firm footing on reality. It also keeps wasting the little time and energy you have left on lost causes, when instead you could be investing them in more realistic, more honourable pursuits.

Real-life story:

One of the most deluded guys I ever met was during my university years. I remember a friend compassionately characterising this deluded guy as being “cursed by God”. Yes, nature did him wrong. The guy was short, scrawny, bald in his early 20s, physically unattractive, intellectually unimpressive, and he had the silliest cackle that would make Kamala seem like a classy Bond girl. He also had a kyphosis, a weird limp, and he looked a bit creepy. He wasn’t rich, wasn’t charismatic, wasn’t smart. He truly had it all against him.

Yet he was the most relentless flirt I had (and have) ever seen. He proudly boasted that he never approached women who weren’t 10s, that anything below that wasn’t good enough for him. And truly, whenever he was in the vicinity of an ethereal beauty or a literal supermodel, he would walk up to her and offer her a cheap compliment, a flower, a chocolate, a piece of paper with some cheesy poetry he stole and claimed to be his. Anything.

Some viewed this as courage, an admirable quality and virtue. But it wasn’t. It was self-delusion. There is a fine line between bravery and stupidity, proven by an unending roster of military “heroes”.

Not one of his efforts to attract a knockout girl ever worked. None. Whenever he approached them, they were awkwardly polite with him, trying to reject him softly. Some even found him cute, not as an “attractive cute”, but cute in the sense of a boy with a mental disability. They found him adorably pitiful and a non-threat. For a woman to truly be attracted to and admire a man, she must perceive him as a potential threat.

I remember he had an obsession with a particular blonde at uni, whose beauty was truly otherworldly. She was so pretty she belonged in an art museum, so heavenly that nobody should have been permitted to touch her (and this coming from me, who’s hard to impress). Yet he hoped, no… he counted on the fantasy that he’d somehow win her over one day. He confidently kept saying that all his approaches, all his sweet talk, would slowly win her heart because no one else had the guts to approach her. Yeah, as if some rich guy with an Apollonian physique wouldn’t one day just stroll by and pick her up like that. She would settle for nothing less.

But all those years of trying… of grasping at straws, and nothing happened. He just kept making a fool of himself, becoming a spectacle, an object of ridicule. It was hard to respect him because he surrendered his dignity in his refusal to boldly accept his realistic limitations. He didn’t even feel the need to improve himself, to work out, to read, to develop gainful skills, to commit to virtue.

So, our guy in this example wasn’t brave or self-reliant; he was pathologically deluded, denying reality, going after things that were beyond him. He was chasing rainbows: top-quality women with the ability to secure top-quality men. These women were objectively way out of his league, not only because he was unattractive and mentally crippled, but because he was unethical, too. For him, women were objects, commodities. He was not only dishonest with himself but with others too — he used to carry with him a photo of a squad of special forces pawns in balaclavas. He used to show it off to the women with whom he was “flirting”, claiming he was one of those masked soldiers, expecting to impress. And he had laughingly admitted this ruse to me, probably imagining himself to be devilishly astute. But in the end, he was making a fool of himself. Nobody bought it.

The length of your reach

It’s one thing to be self-reliant, to understand that you don’t need external validation, and to possess self-esteem regardless of your capabilities, and it’s another to live a delusion of your own making, imagining you deserve treatment for qualities that don’t belong to you.

Not knowing the length of your reach is not only dangerous, but it also disgraces and humiliates you. And it deprives you of viable opportunities as you waste your focus on the unattainable.

This is why in competitions we have weight classes, age classes, sex divisions, ability divisions, and all kinds of other recognitions of people’s limitations, not as excuses, but as realistic acknowledgments of relative performance, rather than nominally absolute performance. Relative performance is more admirable and meaningful.

It’s not how well you perform; it’s how well you perform within your capacity to perform.

People need to know themselves and acknowledge their capabilities, their limitations. The guy in the above example was punching above his weight, biting more than he could chew. This way, he was wasting his time, energy, and mental clarity on unachievable goals when he could have diverted his focus to more meaningful and more achievable pursuits.

Sisyphus

Toxic motivators keep shaming you with the ridicule and stigma of “giving up”. They slyly imply that you never tried hard or long enough, but this is bullshit. Sometimes you just work too hard for no return, squeeze too much for little juice. Hard work isn’t smart work.

Such evil people masquerading as “inspirational mentors” prefer to deny your efforts and keep you in a Sisyphean loop, keep you wasting more on top of what you’ve lost. Sometimes, the most courageous, difficult, and wise thing to do is give up.

With the stigma of “the quitter”, you get entangled needlessly in a Sisyphean loop, thinking yourself to be successful for not quitting when in fact you’re the biggest loser for hopelessly hoping for the impossible.

Sometimes, quitting is the bravest, hardest, and most successful thing you can do.

The question is having wisdom and discernment to know when it’s time to give up and when to keep on going. Only you and people who truly care for you can know this

Giving up gracefully

Quitting and not playing along (in a game that is rigged, no less) is a prudent strategy. In the Star Trek TNG episode ‘Future Imperfect’ [SPOILER ALERT], Riker finds himself inside a simulation… within a simulation. When he figures out the first simulation, he gets angry and reactive, and the simulation, having failed, collapses to reveal its overarching reality. When he realises that that too is a fake reality, he simply stops playing along, refusing to take any reality seriously anymore. He gives up trying, since he understands that whatever he does is meaningless and unfair. He understands that he finds himself in someone else’s game, who happens to also make the rules. He understands he is powerless to do anything about it. So he gives up, not in despair, but in dignified defiance.

Dignity

There is no “free will” in your attempts to succeed. It’s hubristic to presume you have much input in your quest towards success instead of recognising that opportunity, that it is all down to luck. It’s embarrassing to lack the humility to admit that even our supposedly “free” choices rely on a superior intellect that is randomly acquired.

When life consistently teases you with promises of success, and you just can’t seem to be able to succeed, then you should first recognise this pattern, and then consider whether you can do something differently, or just keep doing the same thing expecting a different result. Even animals can recognise patterns and amend their behaviour accordingly.

In the video above, a farmer teases the cow with food. The moment the cow turns her head to eat the food, the farmer pulls it away. This is an allegory for life. The cow then falls for it a second time. Not for a third, or a fourth, though. She’s learned. She understands that getting the food is impossible, so she gives up trying, refusing to give her tormentor the pleasure of tormenting her with unachievable teases. So, she forfeits the off-chance of getting some food so that she can retain her dignity.

Learning from patterns is a sign of intelligence. Cows are more intelligent than the average voter.

He will win who knows when to fight and when not to fight.

If a battle cannot be won, do not fight it.

~ Sun Tzu, The Art of War

There’s dignity in knowing when to give up, which battles are not worth fighting. There’s integrity in knowing when you are defeated. This is not defeatism; this is courage to accept reality, and also warranted optimism due to knowing your limitations without compromising your self-esteem, but also due to the fact that you can divert your attention to more achievable and realistic endeavours.

Defeatism is giving up when you have the means to win, but choose the conveniences of needless submission just because it’s easier than conflict. Defeatism is choosing lazy convenience, even when convenience leads to destruction. Defeatism is avoiding conflict even when conflict ends up being positively constructive and win-win.

Key takeaway

Sometimes, it’s best to give up on fooling things, on hollow hope for things that aren’t even virtuous or meaningful; not in the grand existence of things.

Perhaps this is what Buddhist-like ideologies mean when they teach detachment: Cut your losses from a bad emotional investment in this reality. It’s not worth it.

Sometimes it is truly too late. Sometimes it’s OK to say “I can’t” and “I’ll never be able to”, because as soon as you close one door, you are able to open many more.

Next up: ‘How to know when to give up and when to keep going’.

They act like giving up is "taking the easy way out." Sometimes the most difficult thing to do is to give up. You have to convince yourself that you won't win

Remember Chuddah. "nothing ever happens."

Excellent. Had to do this several times.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CG2cux_6Rcw