Excuses vs. Explanations

Accountability with extenuating circumstances

People seek absolution for their mistakes all the time. They commit hurtful acts to themselves and to others, and then they expect exoneration based on deterministic factors that led them there.

While we are all the consequence of determinism, this doesn’t free us from accountability. For example, child molesters tend to be victims of child molestation themselves. While they deserve compassion for what they had to go through, this does not excuse their actions. This is what adulthood means: self-accountability and control over the self. This is why we can’t hold children accountable for their mistakes: children are innocent, pure, trusting, impressionable, manipulable, and unable to control themselves. This is why parents are instead accountable for their children.

Adults must be responsible for their mistakes and crimes because it was within their power not to do those things, regardless of the deterministic factors that compelled them towards that direction. Plus, no one else can pay for their mistakes other than they, the people who made them. Yes, they deserve acknowledgement for the abuse they had gone through when they were innocent (the abuse that turned them into monsters), but look at what they did: they mimicked the abuse they endured against innocents of all people, just like they were. They transferred the same horrors they had to live through as innocents onto others who are still innocent. How the innocent become corrupt…

Determinism does not mean pardon and justification of atrocity. We don’t need excuses: we need explanations. We need to recognise psychodynamics, not to absolve crimes, but to be able to prevent them in the future.

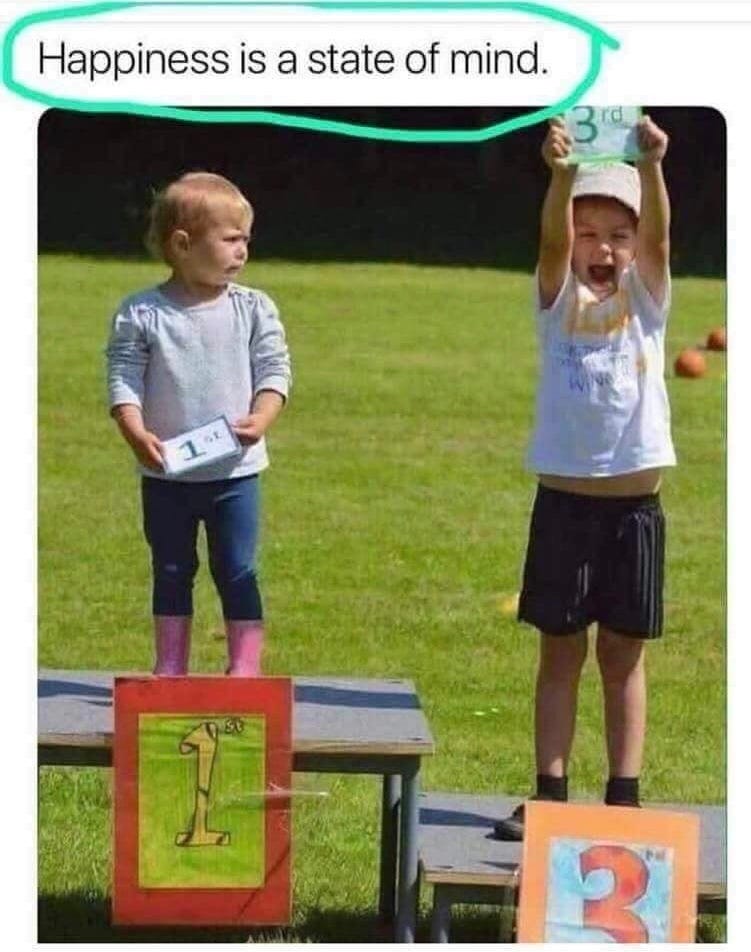

Take a look at this meme, which I absolutely loathe:

Pretty simple, right? The kid in first place is crying while the kid in third place is celebrating. The sly inference is that the first kid is ingrateful, negative, pessimistic, spoiled, and hard to please, while the third kid is positive, appreciative, and better all around. “Happiness is a state of mind”, as if any innocent child would choose to be miserable. This lack of discernment and empathy, this blanket blind “justice”, is why the world is so hostile to itself.

Consider: why would a child in the first place be crying, and appear to be envious of the child in third place? Why was Fernand jealous of Edmund, when Fernand had apparently everything, while Edmund was poor? Do I need to spell it out?

Nurturing parenting.

While Fernand “had everything” (meaning money), he also had a horrible father. At best, his father was dismissive and neglectful. No amount of money can buy out a child’s need for good parenting. Edmund, on the other hand, was poor, yet he had a nurturing, encouraging father, the kind who was always there. We can tell in the story how much father and son loved each other. Can’t say the same about Fernand and his tragic relationship with his father… And this is why, when they were children, Fernand, who got a pony for his birthday, was jealous of Edmund, who was happier getting a mere whistle. Isn’t this the same case as the meme?

In this patronising meme (which, by the way, promotes toxic positivity), nobody pauses to consider the hellish life of a child who achieves first place, in whatever it is he was competing in, and then cries, apparently envious of the child in third place. Compassion, anyone? Instead of berating the kid on top of it all, use that big brain of yours and try to think what the backstory is. Take all the time you need.

The kid in third place is celebrating because he is celebrated. His parents showed up, and he is witnessing his parents’ enthusiasm for his third-place accomplishment. The kid in first place is probably wondering why his parents never bothered to show up, or if they did, why they aren’t as happy for him as the parents of the third kid seem to be. The first kid is wondering how worthless he must be if a first place isn’t enough to make his parents as happy as the other kid’s parents for a lesser position.

I know this feeling. I’ve been there many times. When I was 12 years old, I was honoured in school for being one of the best students in school. I was called on stage to receive an award at an end-of-year celebration. All the other parents were ecstatic about their children’s accomplishments. Even the kids who never won anything always seemed to have parents who gave them some attention, some love, something other than berating and commands. But my parents? Could they at least be happy for the right to brag to the other parents about the accomplishments of their son? I remember my mother suggesting to my father, “Say bravo to your son”. And my father’s response? “If he wanted a bravo from me, he should have worked harder. He still got two Bs over the year. He could have worked harder, and he didn’t”. At the time, I thought this was OK; I didn’t deserve parental love, anyway. Looking back, I can safely wonder what a piece of shit I had as a father.

Growing up, I was the crying kid in that meme. No, happiness is not “just a state of mind” that you can turn on and off on a whim. Besides, what random, deterministic factors determine this state of mind?

I remember wondering why so many parents loved their children, spent time with them, engaged in conversations with them, even when those children weren’t good students, even when those children weren’t as well-behaved and obedient as I was. How worthless was I to not deserve half as much? So, I grew up convinced of my low worth, carrying low self-esteem, leading to all the life-determining bad choices that came with that. It’s never “just a state of mind”. The state of mind comes from somewhere.

My point here is not to show condescending pity for people, nor to excuse them for their bad choices in life, even if those choices were the consequence of trauma. The point is to explain, to understand the causation, to be able to avoid it in the future. We can’t solve problems if we deny their existence. If you keep saying “happiness is just a state of mind”, ignoring the reasons that put people in negative states of mind, then, guess what, you’ll never address what makes people miserable.

And there’s something else too.

If you show compassion for people’s extenuating circumstances, if you give them credit for the bad hand they were dealt, then you help them differentiate themselves from their failures. You don’t absolve them or pardon them with excuses; excuses mean that making more mistakes is OK, and you’re not helping them.

Instead, you hold them accountable to signify that mistakes were and are mistakes, but you also show compassion and understanding as to why they made those mistakes, how they found themselves in a difficult position, and why they felt compelled to act a certain way. They still must pay for their mistakes (who else must?), but if you also acknowledge the unfortunate circumstances that led them there, you detach their self-image from their identity-determining trauma. You help them stop identifying with their trauma-driven mistakes. You encourage them to change, to revert to their true, innocent, healthy self, to finally grow without being defined by their trauma, nor the mistakes they made due to that trauma.

If anything, giving people the benefit of credit for their trauma, their exonerating circumstances, is your best chance at encouraging them to want to make amends. If you keep blaming them, you further entrench them into the identity of the loser, the criminal. And you’ll get more of that. Good job!

Be more compassionate and less condescending. Give people the gift of explanation, but not of excuse. Give them credit for the bad hand they were dealt, and you thus help them improve.

Give them explanations, not excuses.

Keep them accountable, but don’t blame or punish them.

Show them a path to meaningful redemption instead of unconstructive retribution.

The bottom line

Hold people accountable for their mistakes, but don’t blame them.

Their mistakes are not their fault; they are simply their responsibility. Give them empowering responsibility, not debilitating punishment. Give them explanations, not exonerations or excuses.

What’s the difference?

If you begrudgingly blame them instead of holding them accountable, you insist that they are defined by their mistakes. You convince them that their mistakes are an integral part of their being, their identity, their core self, which is why they will carry on feeling they deserve the eternal stigma of blame, guilt, and scorn. So, if you help them identify with their mistakes, they have no other way than to entrench themselves further into their destructive identity, to keep making mistakes to validate the only self-image they know: the destructive, traumatised, hopeless one.

How are you helping them then? How is blaming them encouraging them to change? How are you helping them see who they could have been had they not experienced their determining trauma?

Explanations (not excuses) give those willing to improve the benefit of the doubt while still holding them accountable. You don’t condemn them, which means you acknowledge their potential for good. You simply hold them accountable, which means you respect their ability to stay in control of their actions, their power over what they did, and therefore, what they can change from here on end.

Instead, excuses and exonerations grant undeserved pardons for mistakes and abuses, which means encouraging such self-destructive behaviour. Excuses also deprive them of agency, which is detrimental to their confidence and self-esteem. Excuses tell them that there is nothing they could have done or can do differently. Excuses keep them in the same destructive mindset by taking away their responsibility, their agency, and their power. If you give people excuses, you refuse to recognise their power of control over their will. You thus become an enabler of destructive behaviour.

Besides, if you give people, not condescending pity, but respect, and some credit they deserve for enduring a bad hand they were dealt, then perhaps you’ll offer them the gift of confidence and self-assuredness, the drive towards whatever redemption remains possible for them.

Hold people accountable while recognising their extenuating circumstances. Admit they didn’t deserve the bad hand they were dealt while encouraging them to redeem themselves, somehow.

Shouldn’t be too complicated.

Love this 👌

Being a caring, competent, loving and knowledgeable parent (about factual child-development science) should matter most when deciding to procreate. Therefore, parental failure seems to occur as soon as the solid decision is made to have a child even though the parent-in-waiting cannot be truly caring, competent, loving and knowledgeable.

Parents, including fathers, really need to be emotionally sound/strong AND knowledgeable about child-development science. I find there remains a naïve perception resulting in the perilous implementation of procreative ‘rights’ as though the potential parent will somehow, in blind anticipation, be innately inclined to sufficiently understand and appropriately nurture the child’s naturally developing bodies, minds and needs.

In Childhood Disrupted the author writes that “[even] well-meaning and loving parents can unintentionally do harm to a child if they are not well informed about human development” (pg.24).

Although society cannot prevent anyone from bearing children, not even the plainly incompetent and reckless procreator, it can educate all young people for the most important job ever, even those intending to remain childless. And rather than being about instilling ‘values’, such child-development science curriculum should be about understanding, not just information memorization. It may even end up mitigating some of the familial dysfunction seemingly increasingly prevalent in society.

If nothing else, such curriculum could offer students an idea/clue as to whether they’re emotionally suited for the immense responsibility and strains of parenthood. Given what is at stake, should they not at least be equipped with such important science-based knowledge?

Crucial knowledge like: Since it cannot fight or flight, a baby hearing loud noises nearby, such as that of quarrelling parents, can only “move into a third neurological state, known as a ‘freeze’ state. … This freeze state is a trauma state” (pg.123). And it’s the unpredictability of a stressor, rather than the intensity, that does the most harm. When the stressor “is completely predictable, even if it is more traumatic — such as giving a [laboratory] rat a regularly scheduled foot shock accompanied by a sharp, loud sound — the stress does not create these exact same [negative] brain changes” (pg. 42).

Mindlessly ‘minding our own business’ often proves humanly devastating, especially when child abuse is involved. And some people still hold a misplaced yet strong sense of entitlement when it comes to misperceiving children largely as obedient property.

Yet, largely owing to the Only If It’s In My Own Back Yard mindset, however, the prevailing collective attitude (implicit or subconscious) basically follows: ‘Why should I care — my kids are alright?’ or (the even more self-serving) ‘What’s in it for me as a taxpayer?’